site history

The land of Delprat cottage is full of history stretching thousands of years of Aboriginal, colonial settlement and industrial development.

A common theme of catering to the community and enabling progress through its unique landscape is visible throughout its past.

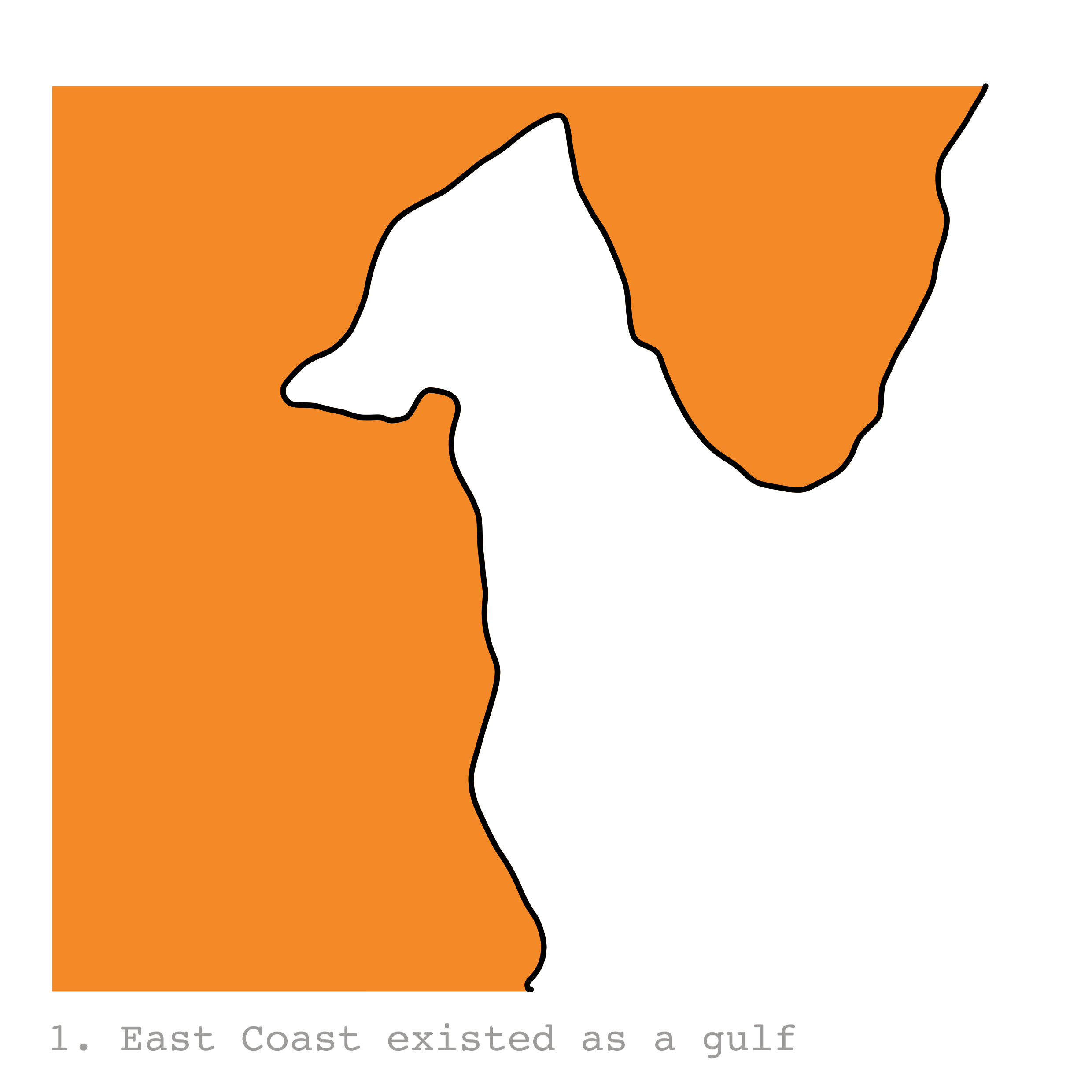

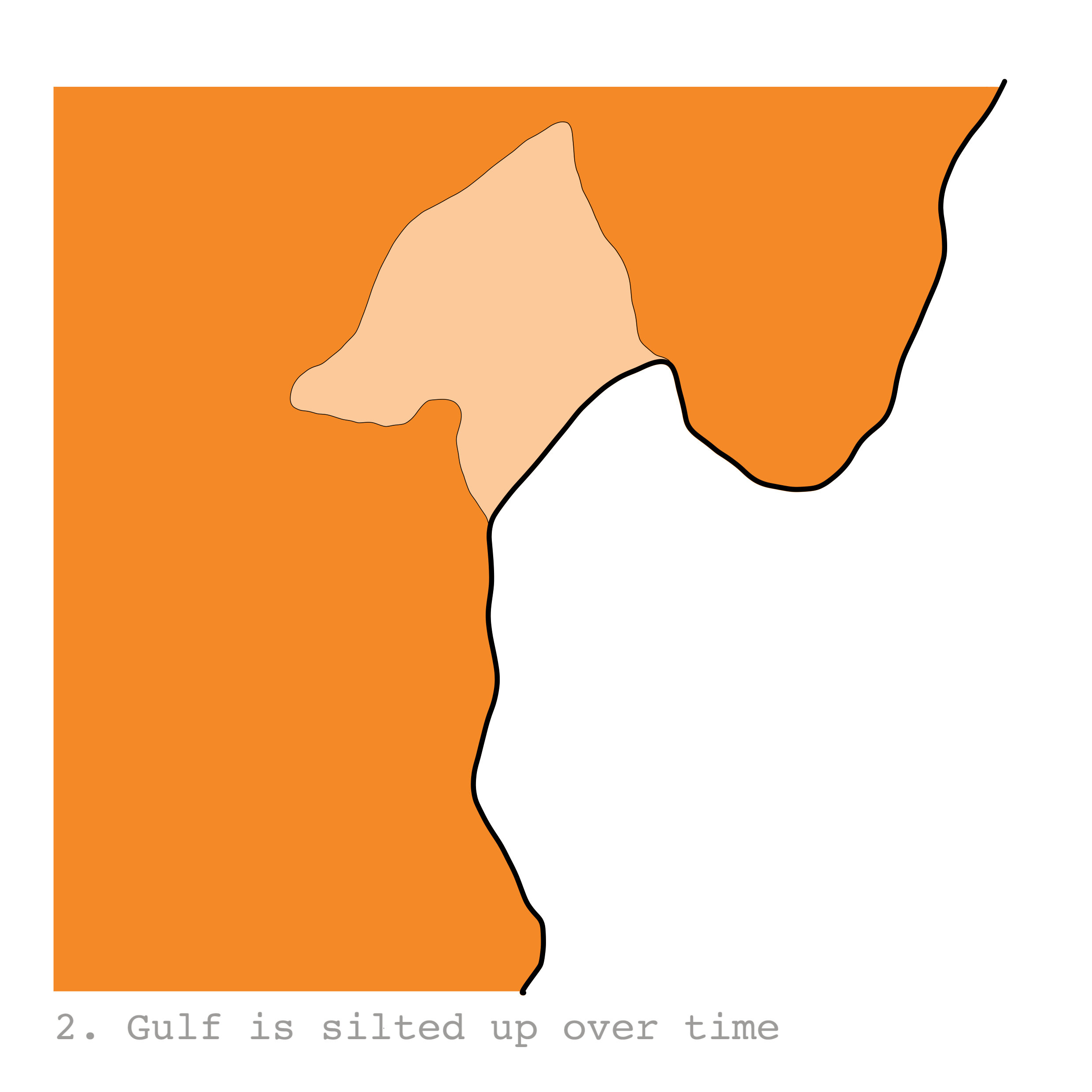

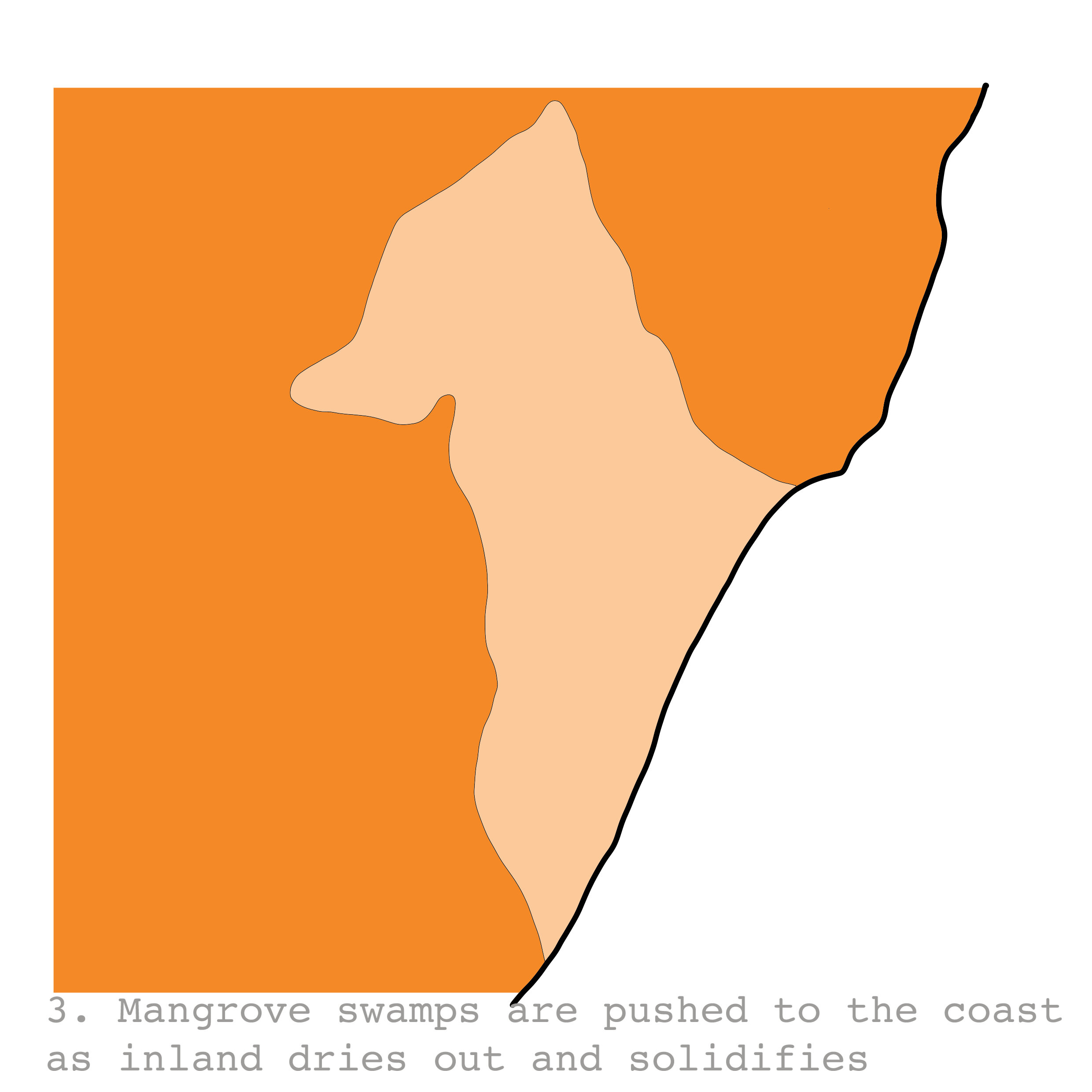

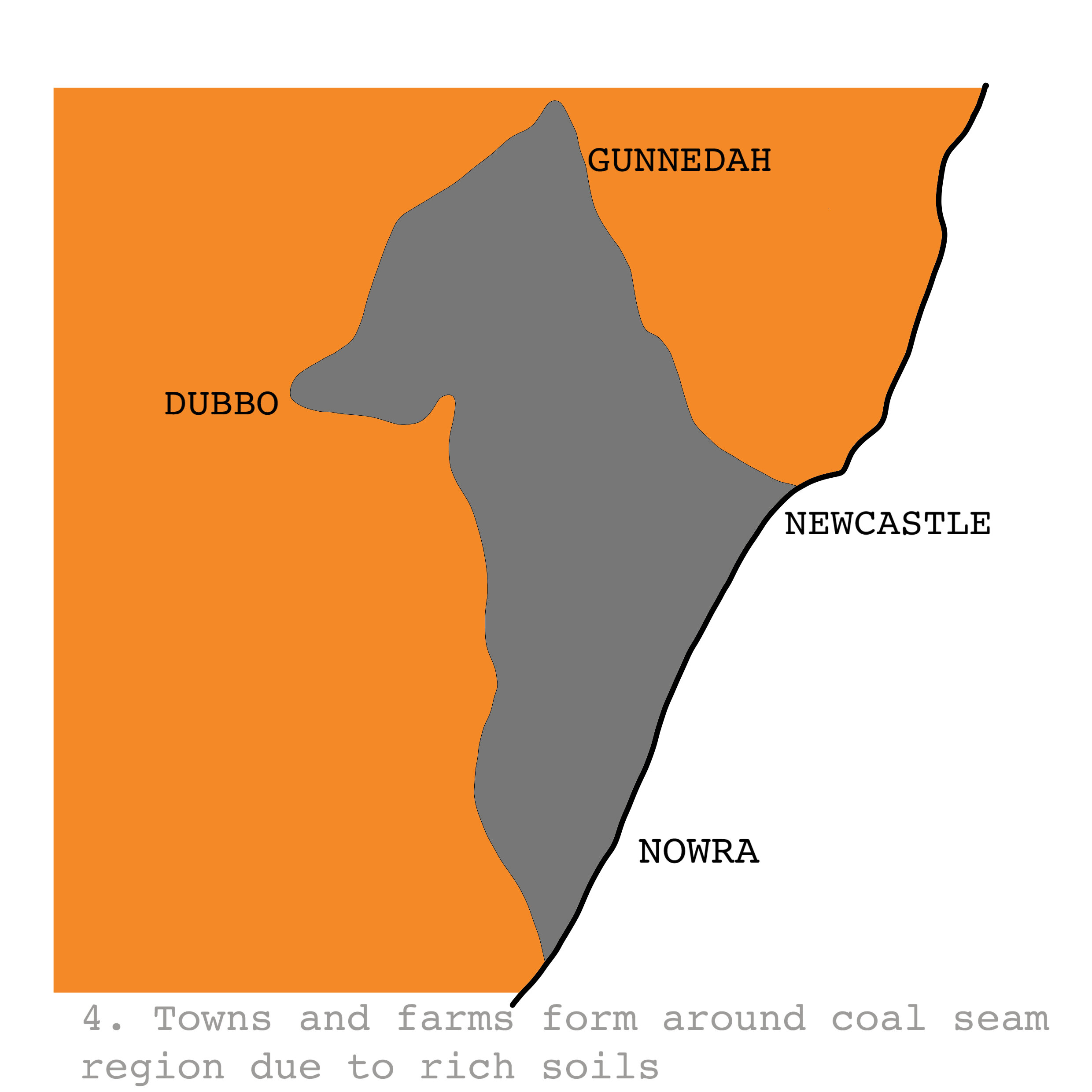

Hundreds of million years ago, the entire Hunter Valley region was covered by ocean water in the form of a gulf that encompasses what we now call Newcastle, Nowra, Dubbo and Gunnedah. Over time, the gulf was silted up by materials to form a mangrove swampland. Compaction of vegetable matter solidified the soil, filling in the Hunter Valley until a band of mangroves remained along the mouth of the Hunter River

Indigenous land

The southern bank of the hunter river on which the site stands is first known to be the land of the Pambalong clan of the Awabakal nation [i]. Early settlers and surveyors noted several campgrounds shared with the Sugarloaf Tribe, a grand corroboree (later turned cricket pitch), burial sites and ceremonial grounds in the surrounding area[ii].

First colonial exploration in 1801 of the Hunter noted many natives, fires, canoes, fishing, preparation of vegetables and bountiful natural resources. Lt-Col Paterson remarked, “the quantity of oyster shells on the beaches inland is beyond conception, they are in some places for miles. These are four feet deep without either sand or earth.”[iii] These were Aboriginal middens, discarded shells of marine life that built up over many generations.

However by 1837 the impact that settlement had on Indigenous Australians was clear. A missionary wrote to the governor that the Aboriginal population had noticeable and severely shrunk in size, explaining that ‘the decrease of the Black population is not local and temporary, but, general and annual.’[iv] As Newcastle grew and expanded over the decades, the Aboriginal population diminished rapidly.

Thousands of stone Aboriginal instruments, axes, knives, flakes have been found along the riverbanks. Mr. Loch of the BHP Survey Department first located them and alerted amateur archaeologist Cooksey, who sent in samples to Australian National Museum as well as the British Museum.[v]

Cooksey compares the BHP site to an imagined “small factory” of aboriginals making instruments as daily life required.[vi]

Upon inspection of the samples the Director of the Ethnographical department of Australian Museum, W. Thorpe remarked that Newcastle was “fortunate in being places in a district so full of these relics – to get the same number round Sydney would take many weeks of careful searching”.[vii]

Newcastle newspaper The Voice of the North expands upon the sophistication of tool making possessed by aboriginals along the Hunter:

“Newcastle district is noted for its ancient factory sites. The toolmakers of the Stone Age evidently traded implements with the tribes of the interior and factories were situated on the banks of the Hunter and along the coast to Lake Macquarie. Mr. Cooksey has collected more than five thousand excellent specimens in a few years, and his knowledge of the subject has been availed of by the authorities at the British Museum in London, and by the Sydney Museum. The similarity of the ancient stone tools and their modern steel prototypes is most remarkable. Saws, planes, chisels, knives, axes, hammers and lances were all known to the ancient inhabitants of Australia, and their manufacture is evidence of a very high degree of skill and monuments of their industry and patience”[viii]

Colonial Settlement

Hunter River was mapped by British colonist Lieut. John Shortland on route to Port Stephens on the H.M.S Reliance in 1797, and sights both coal and Aboriginals in the general vicinity of Delprat Cottage.[i] Attempts were made to settle there soon after, and in 1801 loads of coal began to be sent to Port Jackson and Sydney.[ii] International coal exporting began immediately, with these cargo loads of coal traded to India and China respectively.[iii] These early coal miners eventually came into contact with local Aboriginals, usually ending in the demise of the locals and retreat of the settlers.[iv] Eventually “the worst Irish settlers” involved in castle hill uprising, were sent to the hunter river as a convict settlement providing raw resources of timber, coal, salt and lime for the Sydney colony.[v]

The Colonial Government quickly noted the bountiful natural resources of Newcastle. Governor Macquarie writes of “the extensive rich and fertile land found… along the three principle sources of the Hunter River”.[vi] A raw resource port that shipped supplies to the other colonies was envisioned. After convicts started easily escaping through the evolving trade network, the government declares Newcastle a free city in 1821.[vii] A large amount of clearing done by convicts for timber allows for easy settlement.

In 1822 John Platt becomes the first free settler in Newcastle.[viii] He is given a 2000-acre land grant over current day Mayfield. Platt builds an estate along Southern arm of Hunter River, where the current Delprat Cottage site is and planted wheat for grinding into flour for food with a mill he built.[ix] Early local Braye recounts memories from interviews with early settlers, giving us a rare view into the flora of Platt’s estate before the development into a steel works:

"immediately behind the Mangroves fringing the River there was a small belt of dense tropical brush, consisting of wild native figs, black apple trees, myrtle, cedar”.[x]

Besides the abundance of vegetation, Platt also mined for resources. Oyster shells were extracted from Aboriginal middens for the purpose of making lime. Platt is also believed for having constructed two coalmine tunnels underneath his mill.[xi]

The riverside by Platt’s hill quickly become a lush garden and picnic area known as ‘the Folly’.[xii] The folly was home to large orange orchards and vines for winemaking. Chinese immigrants also grew vegetables along the riverbanks and would go door-to-door selling their harvests.[xiii]

The Australian Agricultural Company had a monopoly with the Government on coal extraction in Newcastle at the time. After Platt’s death, the Australian Agricultural Company purchased the land from his son in 1838 in order to remove competition and ensure sole control on mining.[xiv] Besides a house built for the company director in 1885, the land largely fell into disuse.

This house on the hill was acquired by Catholic Church and was turned into a boy’s orphanage in 1933.[xv] It functioned as a home and school, whilst the land was used for a farm growing crops and raising livestock.

BHP

With the booming coal mining industry Newcastle had greatly developed by this time and Mayfield became desirable real estate for prominent businessmen to live.[i] Many businesses opened stores, hotels were built and tramlines extended.

Labor Government, after winning the NSW election through promising state industry works, was approached by B.H.P about building a steelworks in Mayfield.[ii] This was accepted, as the government was facing substantial financial and political opposition in stabling a state steelworks.

The. Hon. MARTIN DOYLE: “They have no money!”[iii]

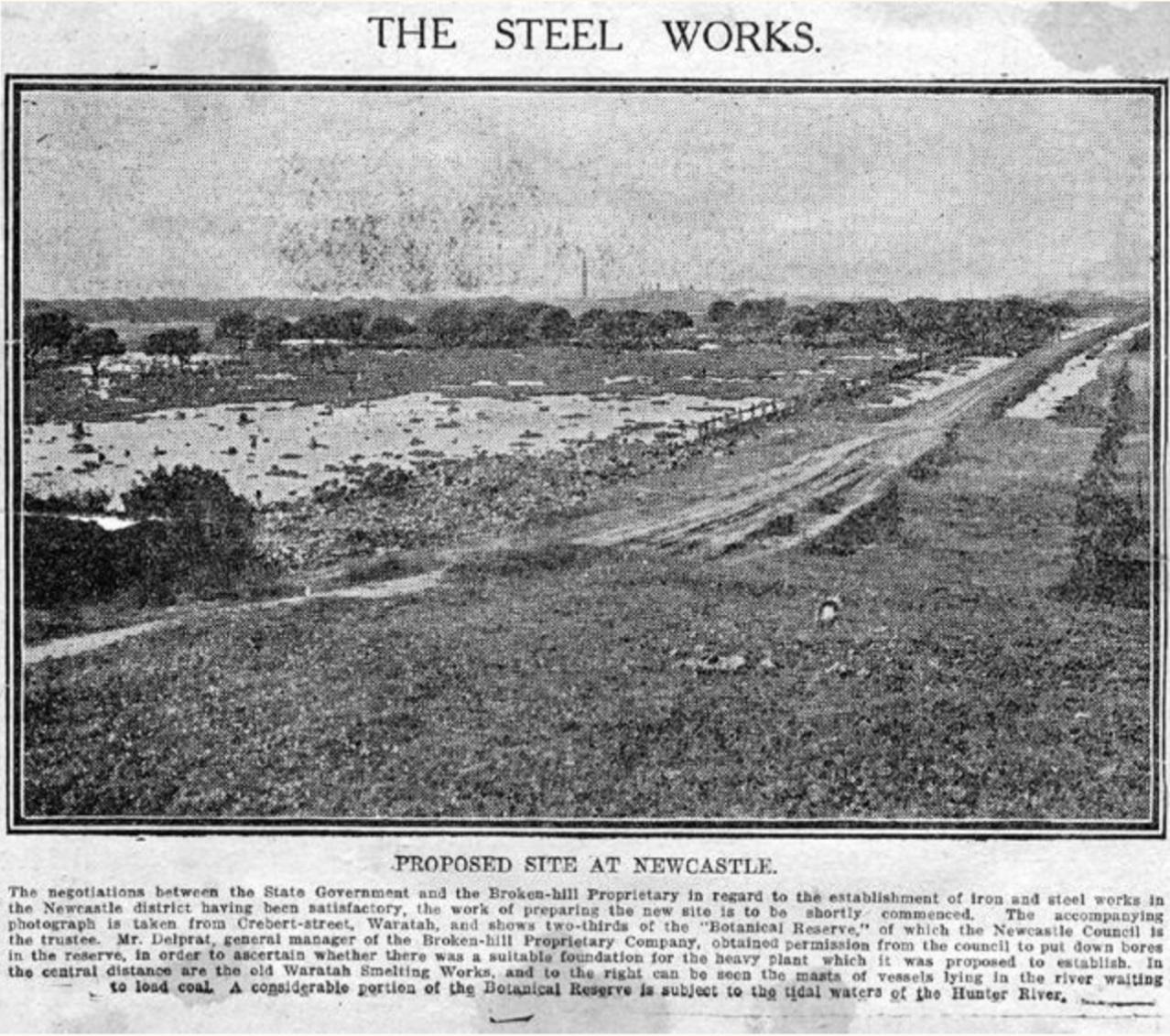

The labor Government was committed to “carry out certain works at the public expense for the purpose of aiding this enterprise.”[iv] This included dredging the channel; using the waste to infill the southern arm of the Hunter River, Platt’s channel, and allowing BHP to acquire land earmarked as Botanic Gardens. This decision would have a substantial impact on the development of Mayfield: “We shall then see in Newcastle the birth of what will almost certainly become the most extensive secondary industry in the Commonwealth.”[v]

In 1914 a cottage was built and named after G.D. Delprat, BHP General Manager and resident of Newcastle who organized the foundations of steelworks.[vi] World War I was declared the same year and BHP began producing for the war effort, with the first steel tapped in 1915. [vii] BHP also supplied steel for the construction of the Sydney Harbor Bridge.[viii]

BHP became the biggest steelworks in the commonwealth in the 1930s, and was of national strategically importance if supply chains overseas were disrupted.[ix] These concerns were realized with the outbreak of World war II, and BHP starts making shells in 1936. By the 1960s BHP was the largest private employer in the entire commonwealth.[x]However decreasing global demand and increased international competition forced the steelworks to reduce output and eventually close in 1999.[xi]

In 2002 the State gets back land as well as $100 million for site remediation, cleanup starts removing carcinogens through thermal desorption, but becomes to expensive for NSW government and they move to cap and fill contaminants to stop flowing offsite.[xii] The steelworks were leveled and demolished. River sludge was with ash and cement to make blocks that are stored in lined facility on Kooragang Island. Only the Delpratt cottage remains in its original topographic and soil cover

Today

Now heritage-listed, Delprat Cottage is owned by the University of Newcastle and is occupied by the Newcastle Industrial Heritage Association who are working to establish a museum.

The UON Delprat Garden team is working hard to grow and sample a phytoremediating garden. Monthly performances within the space have been arranged to occur over the coming year.

References